Parliamentary Procedure and Nebraska Boards of Education

Springtime in Nebraska often finds boards of education making difficult decisions. This is the time of year when boards must decide if they are going to reduce force, how they are going to structure the district’s curriculum and activities for next year, and make myriad personnel decisions. One way we’ve seen boards become less effective when making these tough choices is when they become too focused on parliamentary procedure. People who know the rules—or think they know the rules—often use their alleged know-how as a way to exercise power over the board. "That's out of order" bellows the board bully or the angry patron. "You need to raise a point of order if you're going to reopen discussion on that motion, and you can't do that because we've already accepted an amendment to the original motion." In response, everyone else feels sheepish, looks confused, and refuses to speak. All sorts of petty arguments arise from the ignorance or abuse of parliamentary procedure. This makes boards of education less effective.

The good news is, it doesn’t have to be this way. Let us be clear: there is no legal requirement that boards of education in Nebraska follow Robert’s Rules or any other formal system of parliamentary procedure.

Who Is Robert?

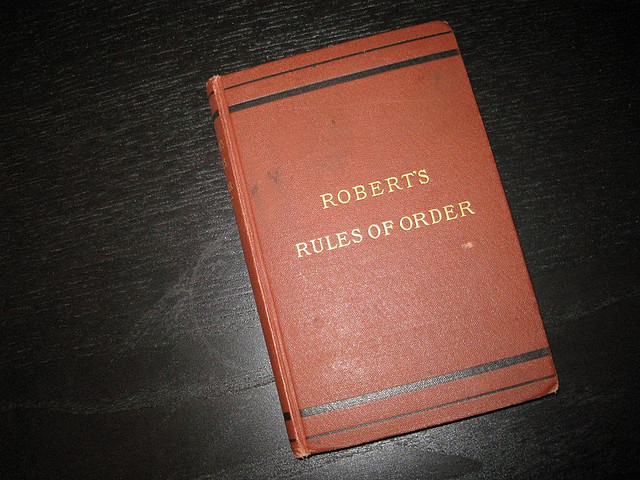

In 1876 Brigadier General Henry Martyn Robert wrote the book ROBERT’S RULES OF ORDER after he had failed miserably in leading a meeting at his church. Robert set out to provide a few rules by which to conduct an efficient meeting, but the project soon took on a life of its own, as questions arose and were answered. The book is over 600 pages long with ROBERT’S RULES OF ORDER NEWLY REVISED IN BRIEF running 200 pages.

And that is the problem. The Rules are complex, and they must be thoroughly understood to be effective. And unless everyone—board members, administrators and patrons—understands the Rules, a self-appointed parliamentarian exerts disproportionate and all too often unhealthy control over the proceedings. Not to mention, public perception of being sneaky or using procedural rules to create confusion is often the impetus of Open Meetings Act complaints to the Attorney General.

What is Required by Nebraska Law?

Happily, Nebraska does not require boards of education to follow Robert’s Rules of Order or any formal system of parliamentary procedure. Instead the Open Meetings Act has a few straightforward but non-negotiable requirements.

1) Every Item the Board Considers Must be on the Agenda

The agenda rule in Nebraska is pretty simple: at least 24 hours before the meeting, any item which will be discussed by the board must be placed on the agenda with enough specificity that an interested member of the public will know that the board will discuss it. That is it. Boards that do nothing other than fully comply with Nebraska law will have very straightforward, uncomplicated agendas, albeit with longer descriptions of each item than most boards currently use.

Robert’s Rules have all kinds of funky rules for the construction of an agenda. For one popular example, they divide meetings up by things like “consent agendas,” “action items,” “discussion items,” and other types of agenda items are doing so voluntarily. There is no such requirement in Nebraska law, and boards should be careful that the use of those divided agendas (especially “consent agendas”) does not lead to insufficient descriptions required of all agenda items according to the Open Meetings Act.

We discourage boards from engaging in any of this complexity as we believe it can be misleading to the board and to the public. For example, if your board has a motion to approve the agenda and it fails, what happens next?

You cannot add items to the agenda (although the board can table or remove items). If the board has labeled an item as “discussion” does that mean the board can’t take action on the item? Under the Open Meetings Act requirements, the label of the item doesn’t matter; all that matters is the sufficiency of the agenda item and then you can take action. However, all of the formulaic requirements of Robert’s Rules create uncertainty and distraction for the board. It also is very frustrating for patrons.

2) Formal Decisions Must be Made by a Roll Call Vote in Open Session

The second rule for Nebraska public meetings is as simple as the first.

Formal decisions must be made in open session by roll call vote. There is an exception for electing board officers (which can occur by secret ballot) and there are some unique procedures for collective bargaining and other types of legal negotiations. But by and large, boards will not go wrong if they simply make every formal decision in open session with a roll call vote.

Again, Robert’s Rules have all kinds of limitations and traps about motions and voting. The person who makes the motion must vote for it. The board president cannot second a motion. The motion can only be amended with the consent of the person who made it. And on and on it goes. None of that is legally required in Nebraska and again, we find that these sorts of rules make life harder, not easier for boards of education.

What is Best Practice?

We believe that boards work most effectively when they follow a consensus- based decision making model, rather than a rigid parliamentary one.

Board presidents must maintain firm control of a meeting and be willing to tell the long-winded individuals (be they board members or patrons) to stop speaking so the more reticent can get a word in edgewise. But they should not dominate the meeting through procedural rules. Motions should be stated as simply and precisely as possible. If possible, we like the agenda to include sample motions that may be modified at the meeting. This is especially true for closed session. Having a draft motion helps board members to be more focused on what they are being asked to decide and enables them to make changes quickly without having to “start from scratch” on the revised motion.

As the board considers the agenda item, the relevant ideas should be passed around and the pros and cons are discussed by board members. In high functioning boards, open discussion among board members is not viewed as a negative but at the same time, board members do not use discussion to attack the administration, staff, or each other. Legally it does not matter if the discussion occurs before or after the motion, second or amendment. Allow us to blow your minds even further: there is no legal requirement to get a “second” to discuss or vote on an agenda item. What does matter is that the exact wording of the final motion that the board votes on is captured in the minutes. If a general agreement seems to be emerging (this is where good listening and facilitation skills are helpful), the board president can test for consensus by restating the latest version of the idea or proposal to see if everybody agrees. If anyone dissents, the board can return to the discussion to see if the motion can be modified to make it acceptable to everyone. If there is no consensus emerging, boards may want to consider deferring the matter to a later meeting. There is no requirement that the board jump through any complicated hoops – a simple motion to table the item is sufficient.

Last Point: Check Your Policies

Every board member and educator should check their local policies on this issue. Some boards have, unwisely in our opinion, adopted policies that state the board will follow Robert’s Rules of Order or some other type of procedural process. Our best advice is that boards rescind that policy or at least remove any restrictions which interfere with the otherwise very simple requirements of the Open Meetings Act. It should only be by choice that board members must educate themselves on formal parliamentary procedure and agree to comply with the byzantine rules.

Conclusion

We believe that Robert’s Rules is out of sync with today’s norms about how people relate to each other and get things done. The modern model is consensus and collaboration instead of more formal patterns of decision-making from past centuries. Although the Nebraska Open Meetings Act does require boards the follow certain procedures, the law is vastly easier to comply with when boards do not hitch their compliance to 600 pages of parliamentary procedure rules.

If you have questions about board operations or any other education law issue, contact your school’s attorney or Karen, Steve, Bobby or Tim.